When

a team from Tulane University sent a batch of protective clothing and

equipment to help workers fighting an outbreak of Ebola virus in Sierra

Leone last month, they were fairly confident the 300 or so packs would

be enough for a good start.

They couldn’t have predicted what they would be up against.

The World Health Organization says 22 new cases of Ebola virus were

reported in Sierra Leone between May 29th and June 5. WHO counts 81

cases with 6 deaths but Sierra Leone’s health ministry says it has a

total of 95 confirmed and suspected cases.

“This is worse than

expected. I am fearful that it could get much worse,” said Robert Garry,

a virologist and specialist in viral hemorrhagic fevers at Tulane

University. Garry flew to Kenema Government Hospital last month with as

much personal protective equipment (PPE) as he could carry, but he says

they are running out fast.

"We have to ration them," he said.

Robert Garry/Tulane University / Robert Garry/Tulane University

Robert Garry/Tulane University / Robert Garry/Tulane University

Kenema Hospital is

treating 11 patients with Ebola, all being kept in isolation. Six more

have died. With each worker needing a complete change of gown, mask,

gloves, goggle and other protective gear with each visit, that means

supplies go fast.

At least 35

lab-confirmed Ebola cases have been traced to a traditional healer whose

grieving patients apparently handled her body at her funeral and became

infected themselves, Garry says.

The healer had treated

patients just over the border in neighboring Guinea. This cross-border

outbreak is worrying health officials because it's spreading in an area

where people cross from one country into another casually, passing

through large cities on their travels.

Ebola is one of the

deadliest viruses known. It kills quickly, taking anywhere between 50

percent and 90 percent of victims, depending on the strain.

The good news is it

doesn’t spread terribly easily — it requires direct contact with bodily

fluids. But caregivers and health care workers can become infected while

caring for patients, and funeral rituals such as washing a body can

expose more people.

“Community resistance is hindering the identification and follow-up of contacts."

And

if people don’t know they’ve been exposed, they can travel sometimes

long distances to spreads the virus to others when they themselves

become ill. WHO says experts are trying to track down 30 people now.

“Community resistance is hindering the identification and follow-up of contacts,” WHO says.

“They are just

scattering,” Garry confirmed. “It’s very hard to track them down.”

Garry's working with local and international experts to identify cases,

distribute protective gear, train workers and test samples.

"Unfortunately, these

numbers will rise dramatically as cases from the Koindu and Daru regions

are tallied. Reports from the field for villages surrounding Koindu and

Daru are grim."

The outbreak started in Guinea

earlier this year, the first time Ebola had been seen in West Africa.

WHO says at least 21 people died and 48 new cases of suspected Ebola

were recorded in Guinea between May 29 and June 3, taking Guinea’s total

to 344.

With more than 215 deaths so far, the West African outbreak is one of the worst on record.

Ebola first arose in

Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, in 1976. In that outbreak,

318 people were sickened and 280 died, with a mortality rate of 88

percent. The biggest outbreak affected 425 people in Uganda in 2000,

killing 224 of them.

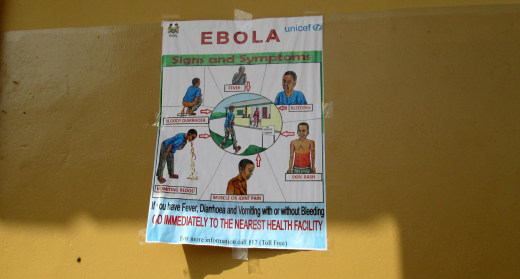

Education is the key to

fighting it. Garry says many people in affected regions don’t

understand it’s a virus and often don’t believe advisories about how

it’s spread. His team is educating health care workers so they can

protect themselves and teach others.

Robert Garry/Tulane University / Courtesy of Robert Garry

Robert Garry/Tulane University / Courtesy of Robert Garry

“They pay attention

once they hear how it’s spread,” Garry said. “The idea is to train these

people here to go back and disseminate the main instructions about the

disease.”

An Ebola infection often looks like malaria at first, so people may not suspect they have it. It later progresses to the classic symptoms of a hemorrhagic fever, with vomiting, diarrhea, high fever and both internal and external bleeding.

With so many bodily fluids pouring from a patient, it is easy to see how caregivers could become infected.

“They pay attention once they hear how it’s spread."

“Ebola

is a disease that scares people and that is perceived as mysterious,

but people can overcome it,” says Marie-Christine Ferir, emergency

coordinator for the group Medecins Sans Frontieres, or Doctors Without

Borders. “Earning people’s trust is essential in efforts to fight the

epidemic."

WHO says six experts and 5,000 sets of protective equipment have been sent to Sierra Leone by various groups.

Garry says his team is

building on years of groundwork. He's been working with the Kenema

hospital for a decade to build its capacity to fight another viral

hemorrhagic fever, Lassa.

Lassa fever is a

serious problem in West Africa, making between 100,000 to 300,000 people

sick every year and causing 5,000 deaths. It can also cause hemorrhagic

symptoms, although it is far less deadly than Ebola, killing 20 percent

of patients sick enough to be hospitalized and 1 percent of patients

overall.

Protective measures for health care workers treating patients with Lassa fever or Ebola are the same.

“We tell them to wear

gloves and to protect their eyes,” Garry said, speaking by telephone

from the hospital. “And we’ve shown people how to do a traditional

burial, only wearing gloves. And you can allow the body to be washed

briefly. Workers have been attentive to the traditions, allowing the

body to be wrapped without exposing people to the virus.”

Genetic analysis of the virus causing the current outbreaks show it’s distinct from

the virus seen in east Africa. This suggests it may be from a local

source. No one’s sure just where Ebola cames from. It can affect great

apes but fruit bats are a prime suspect.

Garry, who was only

scheduled to stay for a couple of weeks, now says he is not sure when he

can leave. "I don't think it's going to be soon," he said.