U.S.

officials leading the fight against history's worst outbreak of Ebola

have said they know the ways the virus is spread and how to stop it.

They say that unless an air traveler from disease-ravaged West Africa

has a fever of at least 101.5 degrees or other symptoms, co-passengers

are not at risk.

"At this point there is zero risk of transmission

on the flight," Dr. Thomas Frieden, director of the federal Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, said after a Liberian man who flew

through airports in Brussels and Washington was diagnosed with the

disease last week in Dallas.

Other

public health officials have voiced similar assurances, saying Ebola is

spread only through physical contact with a symptomatic individual or

their bodily fluids. "Ebola is not transmitted by the air. It is not an

airborne infection," said Dr. Edward Goodman of Texas Health

Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, where the Liberian patient remains in

critical condition.

Yet some scientists who have long studied

Ebola say such assurances are premature — and they are concerned about

what is not known about the strain now on the loose. It is an Ebola

outbreak like none seen before, jumping from the bush to urban areas,

giving the virus more opportunities to evolve as it passes through

multiple human hosts.

Dr. C.J. Peters, who battled a 1989 outbreak of the virus among research monkeys housed

in Virginia and who later led the CDC's most far-reaching study of

Ebola's transmissibility in humans, said he would not rule out the

possibility that it spreads through the air in tight quarters.

"We

just don't have the data to exclude it," said Peters, who continues to

research viral diseases at the University of Texas in Galveston.

Dr.

Philip K. Russell, a virologist who oversaw Ebola research while

heading the U.S. Army's Medical Research and Development Command, and

who later led the government's massive stockpiling of smallpox vaccine

after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, also said much was still to be

learned.

"Being dogmatic is, I think, ill-advised, because there are too

many unknowns here."

If Ebola were to mutate on its path from

human to human, said Russell and other scientists, its virulence might

wane — or it might spread in ways not observed during past outbreaks,

which were stopped after transmission among just two to three people,

before the virus had a greater chance to evolve. The present outbreak in

West Africa has killed approximately 3,400 people, and there is no

medical cure for Ebola.

"I see the reasons to dampen down public

fears," Russell said. "But scientifically, we're in the middle of the

first experiment of multiple, serial passages of Ebola virus in man....

God knows what this virus is going to look like. I don't."

Tom

Skinner, a spokesman for the CDC in Atlanta, said health officials were

basing their response to Ebola on what has been learned from battling

the virus since its discovery in central Africa in 1976. The CDC remains

confident, he said, that Ebola is transmitted principally by direct

physical contact with an ill person or their bodily fluids.

Skinner

also said the CDC is conducting ongoing lab analyses to assess whether

the present strain of Ebola is mutating in ways that would require the

government to change its policies on responding to it. The results so

far have not provided cause for concern, he said.

The researchers

reached in recent days for this article cited grounds to question U.S.

officials' assumptions in three categories.

One

issue is whether airport screenings of prospective travelers to the

U.S. from West Africa can reliably detect those who might have Ebola.

Frieden has said the CDC protocols used at West African airports can be

relied on to prevent more infected passengers from coming to the U.S.

"One

hundred percent of the individuals getting on planes are screened for

fever before they get on the plane," Frieden said Sept. 30. "And if they

have a fever, they are pulled out of the line, assessed for Ebola, and

don't fly unless Ebola is ruled out."

Individuals who have flown

recently from one or more of the affected countries suggested that

travelers could easily subvert the screening procedures — and might have

incentive to do so: Compared with the depleted medical resources in the

West African countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, the

prospect of hospital care in the U.S. may offer an Ebola-exposed person

the only chance to survive.

A

person could pass body temperature checks performed at the airports by

taking ibuprofen or any common analgesic. And prospective passengers

have much to fear from identifying themselves as sick, said Kim Beer, a

resident of Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, who is working to get

medical supplies into the country to cope with Ebola.

"It is

highly unlikely that someone would acknowledge having a fever, or simply

feeling unwell," Beer said via email. "Not only will they probably not

get on the flight — they may even be taken to/required to go to a

'holding facility' where they would have to stay for days until it is

confirmed that it is not caused by Ebola. That is just about the last

place one would want to go."

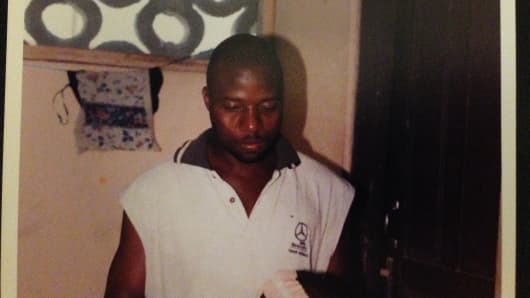

Liberian officials said last week

that the patient hospitalized in Dallas, Thomas Eric Duncan, did not

report to airport screeners that he had had previous contact with an

Ebola-stricken woman. It is not known whether Duncan knew she suffered

from Ebola; her family told neighbors it was malaria.

The

potential disincentive for passengers to reveal their own symptoms was

echoed by Sheka Forna, a dual citizen of Sierra Leone and Britain who

manages a communications firm in Freetown.

Forna said he considered it

"very possible" that people with fever would medicate themselves to

appear asymptomatic.

It would be perilous to admit even

nonspecific symptoms at the airport, Forna said in a telephone

interview. "You'd be confined to wards with people with full-blown

disease."

On Monday, the White House announced that a review was

underway of existing airport procedures. Frieden and President Obama's

assistant for homeland security and counter-terrorism, Lisa Monaco, said

Friday that closing the U.S. to passengers from the Ebola-affected

countries would risk obstructing relief efforts.

CDC officials

also say that asymptomatic patients cannot spread Ebola. This assumption

is crucial for assessing how many people are at risk of getting the

disease. Yet diagnosing a symptom can depend on subjective

understandings of what constitutes a symptom, and some may not be easily

recognizable. Is a person mildly fatigued because of short sleep the

night before a flight — or because of the early onset of disease?

Russell, who oversaw the Army's research on Ebola, said he found the epidemiological data unconvincing.

The

CDC's Skinner said that while officials remained confident that Ebola

can be spread only by the overtly sick, the ongoing studies would assess

whether mutations that might occur could increase the potential for

asymptomatic patients to spread it.

Peters, whose CDC

team studied cases from 27 households that emerged during a 1995 Ebola

outbreak in Democratic Republic of Congo,

Skinner

of the CDC, who cited the Peters-led study as the most extensive of

Ebola's transmissibility, said that while the evidence "is really

overwhelming" that people are most at risk when they touch either those

who are sick or such a person's vomit, blood or diarrhea, "we can never

say never" about spread through close-range coughing or sneezing.

"I'm

not going to sit here and say that if a person who is highly viremic …

were to sneeze or cough right in the face of somebody who wasn't

protected, that we wouldn't have a transmission," Skinner said.

The Ebola strain found in

the monkeys did not infect their human handlers. Bailey, who now directs

a biocontainment lab at George Mason University in Virginia, said he

was seeking to research the genetic differences between the Ebola found

in the Reston monkeys and the strain currently circulating in West

Africa.

Though he acknowledged that the means of disease

transmission among the animals would not guarantee the same result among

humans,

TRANSLATE

TRANSLATE